Author: Mark B. Smith

Publisher: Allen Lane (imprint of Penguin Random House UK)

Edition: 1st Hardback

Price: A$55

Have you ever been told that Russians are naturally politically passive and naturally prone to dictatorship? That the Russian state is inherently prone to terror, violence and necessarily expansionistic? In The Russia Anxiety, historian Mark B. Smith holds up the most common stereotypes and assumptions the average westerner has towards Russian political culture to careful scrutiny. Effectively, Smith’s latest book is a rather robust work of myth-busting rather than history writing as you might be used to it.

While Smith is a historian, this book is more about political culture and international relations rather than history in a traditional sense, especially since the book is arranged thematically. Historical analysis is the primary method and there is no discernible master narrative, like a Marxist or liberal theory underwriting the entire process, which has the effect of making the analysis appear slightly less rigorous and looser and more intuitive. However, the benefit of this is that it allows the analysis to remain flexible, inclusive and unblinkered. It also ensures a lack of hypocrisy, given that this kind of blinkered analysis, as well as path dependence more generally, is what is being criticised throughout the book. Additionally, it is not a comprehensive chronological history and the facts presented are largely utilised in a counter-argumentative fashion intended to reframe typical attitudes, with the facts themselves being generally accepted rather than startling or ground-breaking discoveries.

Smith’s book is divided in three parts. The first part introduces the core concepts that underpin the entire text, as well as providing a very brief lightning of tour of Russian history in general. The second part is the meat of the text, delivering strong analysis on the core assumptions about supposed predisposition to dictatorships, political terror, extremism, empire and the question of Russia’s European-ness. The final, and shortest part deals primarily with how Soviet people engaged with their recent Stalinist past during the Khrushchev Thaw, as well as providing some concluding remarks.

The titular concept, the Russia Anxiety itself is the core thrust of this book and is regularly described as typically having three stages in the cycle, of varying degrees of intensity depending on the exact time period and as something that comes and goes. It’s the seasonal flu of international affairs. The three stages are as follows: fear, contempt and disregard. Fear usually comes from periods, such as in the lead up to the First World War where the German military were concerned about the sheer size of Imperial Russia’s manpower and industrial progress. Contempt comes with events like the Great Terror. Disregard usually follows a Russian defeat, such as the immediate aftermath of the Crimean War or the collapse of USSR in the 1990s. Disregard is especially problematic because, even in circumstances where Russia has diminished power, it is still geopolitically important for balance-of-power relationships and ignoring her legitimate interests, such as bombing Belgrade during the conflict in Yugoslavia or further NATO encroachment simply breeds resentment and mistrust that can strain relations in the short and long term.

In practical terms, the Russian Anxiety acts as a container or complex of negative attitudes towards Russia that are formed principally from orientalising prejudices or selective misreading of Russia’s history, leading to faulty conclusions that filter up to rhetoric and policy decisions that often unnecessarily strain relations with the Russian state. As Smith points out later in the chapter about Empire and Russia’s relationship with Ukraine, specifically over the issue of Crimean annexation, even if the political leaders of NATO countries had less prejudiced attitudes towards Russia, the policy outcome of sanctions likely would have been the same, or at least similar, given issues of international law. You can be rest assured that the concept of the Russia Anxiety isn’t a reason to unilaterally excuse contentious policy actions of the Russian state, internationally or domestically.

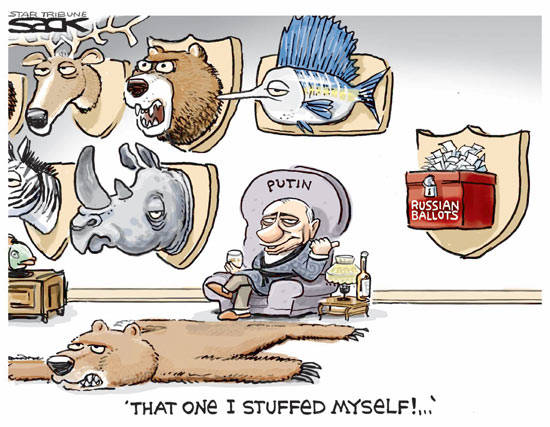

One shortcoming of Smith’s book is that there is little attention paid to how mass media outlets,through film or news reporting, in the West or in Russia itself plugs in to each aspect of the cycle. For instance, in 2014, a Forbes article near hysterically compared Putin to Hitler for the annexation of Crimea, demonstrating Western fears of Russian military (Johnson, 2014), not to mention the alleged interference in the 2016 US elections. For contempt, Western reporting on Russia, such as reporting on the anti-gay propaganda laws serves to denigrate Russians as necessarily backward to liberal westerners feel superior about themselves (Wiedlack, 2017). Anecdotally, based on reporting I’ve seen in commercial news programs in Australia, any news from Russia, with the exception of the FIFA World Cup in 2018 has a tendency to be framed negatively regardless of the situation. The inclusion of this kind of analysis in more detail, while veering off from the broadly historical methodology, would have been a good fit for the subject matter of the book, be especially helpful to non-experts and flesh out the core concept better.

A secondary concept, dubbed ‘instant history’ is something that is quite handy and useful in contexts outside of prejudiced attitudes towards Russian politics. An example of instant history presented by Smith would be tendencies among some historians to say, draw a straight line between Ivan the Terrible’s oprichina and the NKVD during the Great Terror period. The danger of instant history is that while the facts it draws from might be true, the links between them are often tenuous, misleading and are evidence of lazy analysis. Instant history as utilised in the context of Russian history is like taking a small number of outliers in a data cluster and using that as evidence of general trends. It can become even messier if framed in a form of path dependence, since the path would have shaky foundations and would undermine its own analysis.

In the chapter The Dictatorship Deception, Smith tackles the issue of democracy in Russia and why it seems to have not been entrenched in the same way as has been experienced in the Anglosphere and Western Europe. The Speransky Conundrum, one of Smith’s novel terminologies, is essentially the problem of making democracy and autocracy safe for each other, or in other worlds, resolving a dialectical contradiction. Smith goes on to discuss Russia the Muscovite and Novgorodian foundations that provide a viable basis for democracy in the country or the zemstvos and volosts established in the 19th century, the experience of ‘Soviet democracy’ which, while in effect just a pantomime given the obvious lack of choice, still provided a useful feedback mechanism for Soviet elites. He also discusses the experience of the Soviet collapse in the 1990s, which basically disillusioned much of the country to liberal democracy and the ravages of predatory capitalist excess backed by Americans. The fundamental argument from this chapter is the importance of contingency in historical events, an important point throughout the book, and how if forms of autocracy are the innate possibility of the Russian state, then something that is recognizably democratic is also possible. However, while the point is clear and the constellation of facts used to make it sound, the limitations of Smith’s analytical framework are apparent as they lack some broader considerations of sociology, international relations theories or structural analysis.

The next chapter revolves around Russia’s supposedly unique backwardness and barbarism in relation to political violence. Specifically, it focuses on Ivan the Terrible’s oprichina and Stalinist rule, specifically the Great Terror and the gulags. What is generally given little word count is Lenin and Trotsky’s laying the foundations of Terror and oppression during the civil war (Solzhenitsyn, 2007). Nevertheless, there are a few salient points to this chapter. First is that the kinds of violence experienced under Ivan the Terrible and his Oprichina, and with Stalin and the NVKD is that they are extreme outliers in the broad sweep of recorded Russian history. The second point is that the violence under Stalinist rule, whether that be the brutality of breakneck industrialization, the Holodomor or the Great Terror do not come out of some innate and fundamental Russian barbarism, but are the results primarily of Stalin’s personality, style of rule and Bolshevik political culture. The third main point utilises some comparative analysis with Tudor England and contemporary Muscovite rule for instance, demonstrates that for much of Russia’s history, the country’s rulers have acted within normal European parameters; a similar point which drives subsequent chapters as well. This is one way, Smith hopes, to deflate the Anxiety as it puts Russian state actions, historically and in the present, in a broader perspective that necessitates critical self-reflection. Smith anticipates multiple times that this point would be subject to accusations of whataboutism, but such accusations would be wasted as the point is not to deflect from or excuse certain policy criticism, it is simply intended to deflate unwarranted prejudice. The subtitle of this chapter asks if Russia is built on violence and the answer is in short, yes, but in a similar way to how European states, and indeed most states, generally are.

Later chapters deal principally with Russia’s European and Eurasian identity, largely through looking at Russian literature and cases of avant garde artists, with some wordcount dedicated to Eurasianism and providing insight into the ways ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ Europe have been categorised, first through the lens of Christendom and schism, and then through the Cold War lens, which persists today. Another looks at Russia’s imperial heritage using a similar format to the chapter on state political violence, offering insight into Russo-Ukrainian relations and management of difference. Another deals with whether Russia is uniquely warlike or prone to invading other states. The short answer is no and that Russia has mostly been the victim of invasion by others, whether it be the Mongols, Napoleon or Hitler. He also engages critically with the work of Richard Pipes, who is probably one of the most influential Cold Warrior historians of Russia, especially given his political postings. While I cannot go exhaustively into every argument made in the book, these chapters are frequently insightful, well structured and decently written despite a few odd idiosyncrasies.

The final chapters, dealing with historical memory and the Khrushchev Thaw are fantastic, especially for me as it satisfyingly answers the perplexing overall positive attitude Russians seem to have for Stalin that comes out of independent polling results. It also effectively addresses the complexity of dealing with traumatic historical memory and helps understand how people dealt with it in the immediate aftermath of Stalin’s death, often utilising cases of exile playwrights and authors. Soviet science fiction, such as Hard to Be A God would have also been a good example as the substance is effectively Khrushchev’s Secret Speech.

To conclude this review, I will say this about Mark Smith’s book: it is frequently insightful, well structured and does a good job of framing Russian history in a way that counters typical views of Russophobic politicians, media pundits and historians (I’m looking at you, Richard Pipes) in a way that is convincing and cuts through all the sensationalism and romanticism, despite the limited methodology and a few other shortcoming. As to whether it achieves its goal of being an antidote to the Russia Anxiety remains to be seen. If you have any friends with the typical anti-Russian prejudices, put the book in their hands, see what they say. Furthermore, this book would be very useful for any teachers of any aspect of Russian history, or Cold War and contemporary politics, especially in discussions revolving around historiography and historical memory.

References

JOHNSON, P. 2014. Is Vladimir Putin Another Adolf Hitler? [Online]. Forbes. Available: https://www.forbes.com/sites/currentevents/2014/04/16/is-vladimir-putin-another-adolf-hitler/#43fe9e2f237a [Accessed].

SMITH, M. 2019. The Russia Anxiety-And How History Can Resolve It, London, UK, Allen Lane.

SOLZHENITSYN, A. 2007. The Gulag Archipelago: Abridged Edition, United States, Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

WIEDLACK, K. M. 2017. Gays vs Russia: Media Representations, Vulnerable Bodies and the Construction of a (Post)modern West. European Journal of English Studies, 21, 241-257.

Author: Alexander Dugin

Author: Alexander Dugin